Two-Tier Structure

First Assemble then Deploy

This approach distributes Bicep code over two tiers:

- assembler-tier

- core-tier

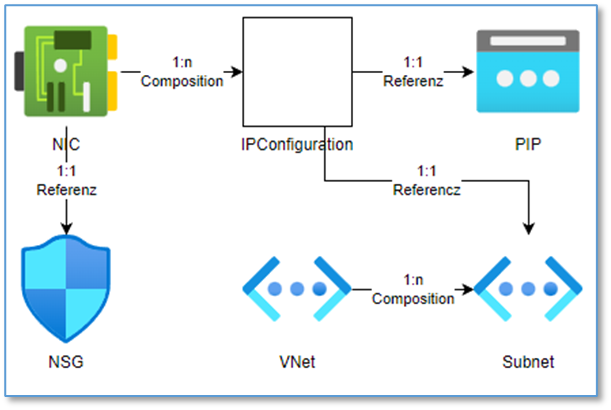

In most cases Azure resources are complex, i.e structured objects. A complex resource may be composed of an arbitrary number of embedded and referenced resources (s.b.).

Just take a look at a network interface card (NIC) as an example:

And this is only a small subset of how a NIC could look like.

So the job is to deploy complex resources composed of other resources, referenced or embedded. Therefore, we create assembler- and core-modules. An assembler knows how to create a complex resource and pulls everything together before consuming the necessary core-modules.

Obviously, the core-modules should be as reusable as possible. A module for creating public IP addresses for example, can be useful in a lot of scenarios. Therefore, they have to be kept quite dumb but with a stable interface.

The assemblers represent the different use-cases. An assembler covers a given scenario by calling the appropriate core-modules. It needs to be told what is to be created, how to create it and what is expected to be already exising.

Every Core-Module gets an Assembler

We create assemblers for every core-module, even if the core-module is very simple and nothing is actually assembled. However, an assembler is useful for at least two reasons:

- the assembler can be used for testing the core-module

- the assembler code demonstrates the usage of the core-module

- this code can be copy & pasted into other assemblers

Parameter-Files represent resource instances

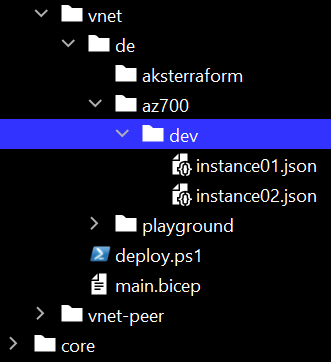

One parameter-file represent one resource instance. This is described in here. The assembler deployment script loops over all parameter files, i.e. instance files, of a given triple (country, domian, environment) and passes them into the Bicep assembler. The following example shows the deployment of two VNets for the triple (de, az700, dev):

Let’s discuss the file “instance01.json”, representing the first VNet instance:

{

"$schema": "https://schema.management.azure.com/schemas/2019-04-01/deploymentParameters.json#",

"contentVersion": "1.0.0.0",

"parameters": {

"vnetName": {

"value": "vnet-az700-01"

},

"vnetProperties": {

"value": {

"addressSpace": {

"addressPrefixes": [

"10.0.0.0/24"

]

},

"enableDdosProtection": false

}

},

"snetSubnets": {

"value": [

{

"snetName": "subnet1",

"snetProperties": {

"addressPrefix": "10.0.0.0/26"

}

},

{

"snetName": "subnet2",

"snetProperties": {

"addressPrefix": "10.0.0.64/26"

}

}

]

}

}

}

Bicep parameter files are explained here. “$schema” and “contentVersion” are a given. Next are the parameters. “parameters” is a dictionary of objects. Each object is named and has a value property.

This parameter file contains three parameters:

- vnetName

- vnetProperties

- snetSubnets

Exposing “Template Fragments” as Parameters

Using complex, i.e. structured or object parameters is probably the most controversial decision because it seems to be against how Bicep wants to be used. For example, Bicep likes primitive values because it allows for quite detailed annotations.

Let me go into the reasoning behind this decision before describing the concept.

Why do I call parameters “Template Fragments”

I’m using peaces a given Bicep resource template as parameters. For loss of a better term I call these pieces “template fragments”. The idea is to pass these parameters into a core module’s resource block as they are. Only assembler logic modifies these fragments, mostly by injecting references to other resources. As such a fragment can be passed down to the core module as is, we can later enhance them as needed without causing a breaking change, as long as we stick to the Bicep resource template syntax.

Why Expose Template Fragments

Using primitive types as parameters results in very long parameter lists. These parameters have to be assigned to properties nested in different levels all over the Bicep templates. Parameter lists like these are hard to handle, because of the sheer number of values and because of the missing context in which they are used. Even when using template fragments, the parameter lists are quite long, give a complex enough resource.

More crucial than being unwieldy, these lists are toxic for reuse. Different instances may need different parameter lists. Removing or adding new parameters requires the signature of the module to change and introduces a breaking change.

Rules for Exposing Template Fragments

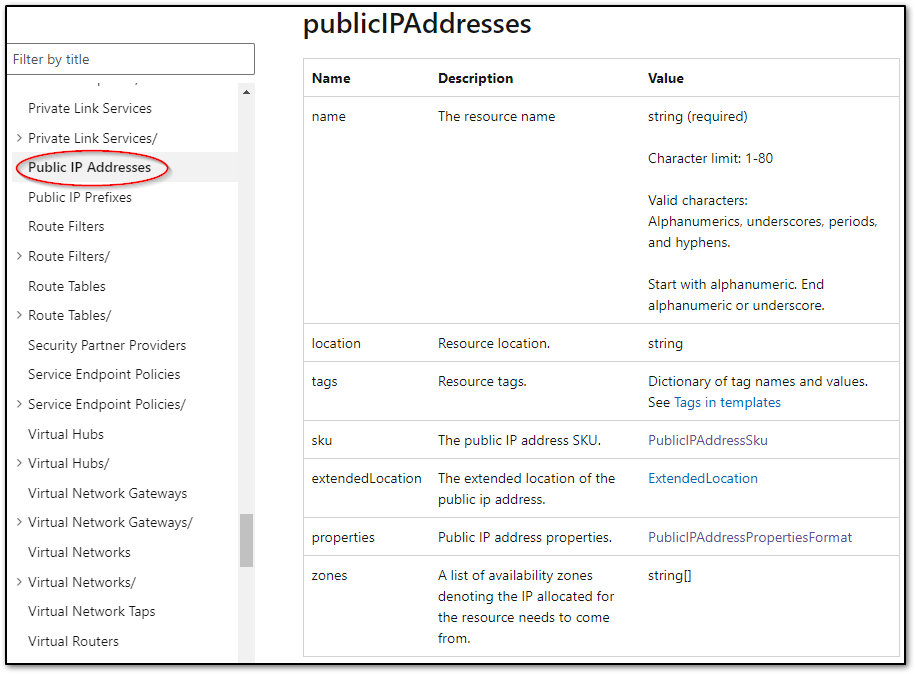

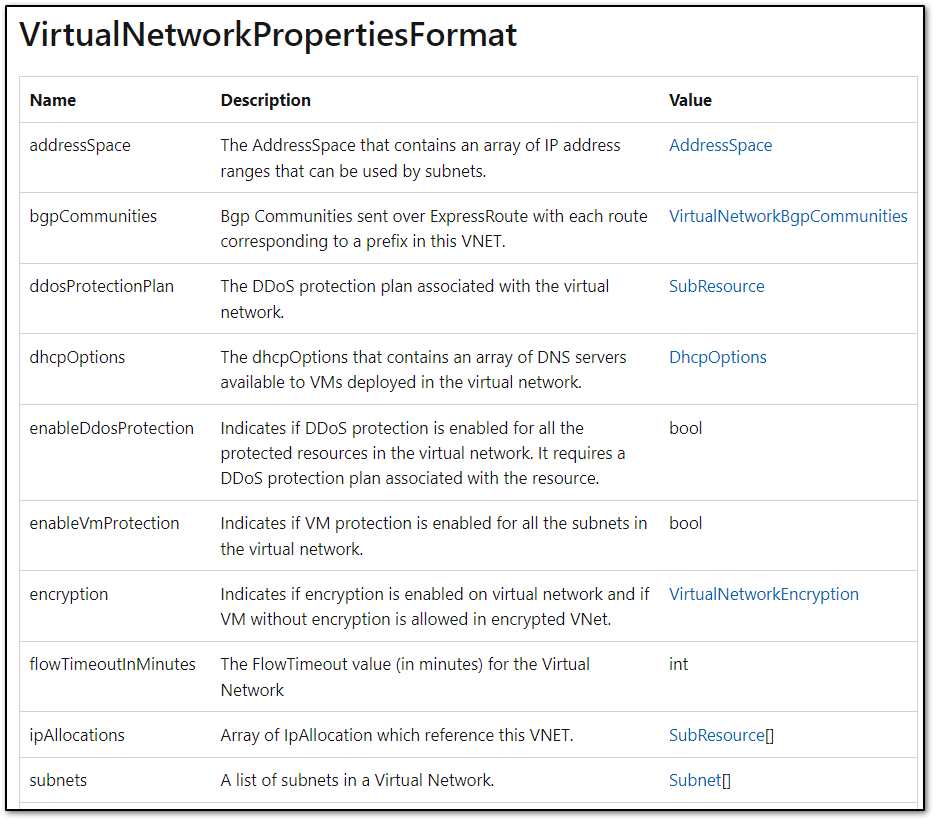

Resource-Type Top-Level Properties as Parameters

My overarching guideline of how to hack resource templates into pieces that will be turned into parameters

is the Azure Templates Reference.

These templates are structured into resource-types: <provider>/<resource-type>@<api-version>.

I use the first level properties of a given resource template as parameters.

Let’s take Public IP Addresses (pip) as an example. Here’s the top-level properties definition of a pip:

These properties are my parameters for describing a pip-instance. The respective parameter file “instance01.json” looks like this:

{

"$schema": "https://schema.management.azure.com/schemas/2019-04-01/deploymentParameters.json#",

"contentVersion": "1.0.0.0",

"parameters": {

"pipName": {

"value": "pip-az700-01"

},

"pipSku": {

"value": {

"name": "Basic"

}

},

"pipProperties": {

"value": {

"publicIPAddressVersion": "IPv4",

"publicIPAllocationMethod": "Dynamic"

}

}

}

}

Please note that because I’m lazy, I only included the properties which I want to configure:

- name

- sku

- properties

Out of laziness I left out:

- tags

- extendedLocation

- zones

Note:

- a complete setup would include the left-outs too, at least as empty objects

- “location” is a special case as Bicep has a function do derive this from the resource-group - no parameter needed

- I’m passing the resource name in - with good naming conventions you could let the module decide on its name

The above parameter file is passed into the assembler “main.bicep”. In this simple case - no child resources, no referenced resources - the assembler just calls the pip core module. The parameters are simple passed through. This is the important part: they are simply passed through. This is possible because the value of such a parameter is a fragment of the resource template. And as long as we stick to this, we can enhance the parameters without breaking things.

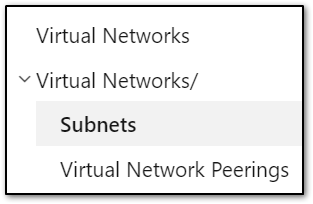

Dealing with child resources

What are Child Resources

Child resources are lifecycle-wise bound to their respective parent. They are created by their parents and cannot exist without them. However they have their own resource type.

The Azure Templates Reference shows child resources like the (take a VNet with its SNets as an example):

These are the respected resouce types of VNet and SNet:

- VNet: Microsoft.Network/virtualNetworks

- SNet: Microsoft.Network/virtualNetworks/subnets

You could say that the SNets namespace is part of the VNets namespace.

Creating Child Resources

The decision here is that the core module is responsible for creating its child resources. This is really a decision, because it could be done differently. Take a look at the documentation again:

Attention: The subnet-array is part of the VNet properties object. So it would of course be possible to specify the subnets as part of the properties parameter in the json file. This is in fact how Microsoft suggests to do it, as described here. My approach seems to cause problems when re-deploying. So maybe I should reconsider, at least for VNets!

As it is, Bicep lets us deploy child resources from outside the parent resource. To do this, the array containing the subnet data is turned into a separate parameter and as this gets passed to the core module by the assembler.

Parameter file:

{

"$schema": "https://schema.management.azure.com/schemas/2019-04-01/deploymentParameters.json#",

"contentVersion": "1.0.0.0",

"parameters": {

"vnetName": {

"value": "vnet-az700-01"

},

"vnetProperties": {

"value": {

"addressSpace": {

"addressPrefixes": [

"10.0.0.0/24"

]

},

"enableDdosProtection": false

}

},

"snetSubnets": {

"value": [

{

"snetName": "subnet1",

"snetProperties": {

"addressPrefix": "10.0.0.0/26"

}

},

{

"snetName": "subnet2",

"snetProperties": {

"addressPrefix": "10.0.0.64/26"

}

}

]

}

}

}

These are the prameters:

- vnetName

- type: string

- name of the VNet

- vnetProperties

- type: object

- everything we want to configure, except the subnets

- snetSubnets

- type: array

- everything we want to configure for the subnets

The core module uses the “outside-the-parent” methode to deploy the complete VNet.

File: core/vnet/vnet.bicep

param location string

param vnetName string

param vnetProperties object

param snetSubnets array

resource vnet 'Microsoft.Network/virtualNetworks@2022-05-01' = {

name: vnetName

location: location

properties: vnetProperties

}

// Subnet als Child Resource, extern definiert

// (da ein Subnet obligatorisch ist, ist das kein bedingtes Deployment)

@batchSize(1)

resource subnet 'Microsoft.Network/virtualNetworks/subnets@2022-05-01' = [for snetSubnet in snetSubnets: {

name: snetSubnet.snetName

parent: vnet

properties: snetSubnet.snetProperties

}]

Note: If child resources are optional, I need an additional parameter to define, whether they should be created in the first place.

Dealing with references

References are resources with a lifecycle independent of any parent. If a complex resource needs to reference another resource, it can either create and than referenced or it simply already exists and gets referenced. But in any case, if the complex resource gets deleted, the referenced resource regularly continues to exist. You can see this in the Azure portal when you delete complex objects like a Virtual Machine for example. You have to decide whether attached (referenced) resources like the NIC shall be deleted along the line.

With references, the assembler has to deal with these situations:

- we want it to create and attach a reference

- we want it to attach an existing reference

- we don’t want the reference to be attached at all

Here is an example:

We want to create a NIC that references an existing NSG. Accordingly, the parameter file describing this NIC at least needs:

- a switch (boolean) telling the assembler that we want to attach a NSG

- a switch (boolean) telling the assembler that this NSG already exists and does not need to be created here

- the name of the NSG, by which the assembler can lookup the resource-id

The assembler can now lookup this NSG and has to inject its resource-id into the NIC template fragment before passing the fragment down to the NIC core-module.

How this can be implemented is described in implementations. Here is the actual code for depoying a VM or a NIC respectively.

| home | design decisions | deployment |